Very High Notes out of Nowhere

29/05/11 07:29

Most players, especially brass players, find it hard to play very high notes without any preparation. Try to avoid having anyone come it in extreme ranges. This also applies to the lowest range in most instruments. If you want to have very, very high trumpets after they have been silent for some time, at least give them a few quiet lower notes so they can prepare. The higher it gets, the harder the embouchure is for brass players because of less space between the harmonics. For very skilled players, very high notes out of nowhere usually are not a big problem, but it always adds a bit of insecurity. Besides, is it plain rude to stress people like that. Usually you can find some way to circumvent high notes out of nowhere.

Comments

Sampled instrument volume

08/05/11 09:50

While any kind of sampled instrument is a great tool and can be very useful for composing, there is one thing that creeps up again and again: Instrument volume.

On many libraries, especially low to mid-price, the development of the overall volume of an instrument is not correctly set. Most instruments have a part of their range where they are pretty quiet as well as a part where they really shine. In some libraries, the whole range of an instrument has the same volume. This leads to lines that can be perfectly heard in the sampled version to not come out at all when played by real instruments.

The best example perhaps is the flute, which is very quiet in its lower register (from Middle C (C4) to about E5), but gets really loud after that. Ranging up to C7 (sometimes even higher, depending on the player), it is very piercing and easily can be heard over the rest of the orchestra. When writing for the flute, keep in mind that it is very ineffective in its lower range. You can use it in this range to add a special shine to strings, but this only works on quieter passages.

The same appies to other instruments as well. Also keep in mind that with real instruments you cannot just crack up the volume to make it loud! You can use unnaturally loud instruments as an effect and this is commonly used in sampled music, but as soon as real people have to play your piece, it won’t work.

On many libraries, especially low to mid-price, the development of the overall volume of an instrument is not correctly set. Most instruments have a part of their range where they are pretty quiet as well as a part where they really shine. In some libraries, the whole range of an instrument has the same volume. This leads to lines that can be perfectly heard in the sampled version to not come out at all when played by real instruments.

The best example perhaps is the flute, which is very quiet in its lower register (from Middle C (C4) to about E5), but gets really loud after that. Ranging up to C7 (sometimes even higher, depending on the player), it is very piercing and easily can be heard over the rest of the orchestra. When writing for the flute, keep in mind that it is very ineffective in its lower range. You can use it in this range to add a special shine to strings, but this only works on quieter passages.

The same appies to other instruments as well. Also keep in mind that with real instruments you cannot just crack up the volume to make it loud! You can use unnaturally loud instruments as an effect and this is commonly used in sampled music, but as soon as real people have to play your piece, it won’t work.

Principles of Orchestration on Northernsounds

14/04/11 11:51

Today I have a link tip for you:

If you want to learn more about Orchestration, you have lots of possibilities at your disposal. By far the best of course is to take private lessons (preferably with me - shameless plug^^), because nothing beats pestering some real person with questions.

The second best approach are books of which there are many, some of them I will discuss in a later post.

One famous book is by composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, called „Principles of Orchestration“. You can buy it as a book, but the fine folks at Northernsounds took the time to painstakingly prepare an online version, which is available on their forum. You get the real deal, with lots of interactive content. Korsakov’s book primarily deals with classical romantic orchestration, but 99% of this applies to film music just perfectly. Reading the book will give you a deeper understanding of how the orchestra works and your music will most certainly benefit from it.

So head over to Northernsounds - Principles of Orchestration and become a better orchestrator!

If you want to learn more about Orchestration, you have lots of possibilities at your disposal. By far the best of course is to take private lessons (preferably with me - shameless plug^^), because nothing beats pestering some real person with questions.

The second best approach are books of which there are many, some of them I will discuss in a later post.

One famous book is by composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, called „Principles of Orchestration“. You can buy it as a book, but the fine folks at Northernsounds took the time to painstakingly prepare an online version, which is available on their forum. You get the real deal, with lots of interactive content. Korsakov’s book primarily deals with classical romantic orchestration, but 99% of this applies to film music just perfectly. Reading the book will give you a deeper understanding of how the orchestra works and your music will most certainly benefit from it.

So head over to Northernsounds - Principles of Orchestration and become a better orchestrator!

Very long breaks in scores

30/03/11 07:11

Sometimes you have scores with very, very, very long breaks for some instruments. This may for example happen with large backing bands only playing during the chorus. You should of course tell these folks when they need to come in again (most notation applications will write one bar and put the number of silent bars in it), but if they have a break of 30 bars or so, noone will actually count!

silent bars in Sibelius

This is where you need to use cues: Look for an easily recognizable part someone else is playing directly before your players have to come in again and write it in the parts in cue notes (smaller notes). The players need to hear the cue part, so choose someone they can hear (very loud, sitting near them, ...) This will help them find the place. Also make absolutely sure the conductor (or whoever may be responsible for leading the players) gives them their entrance very clearly, i.e. by making eye contact one bar before they need to come in.

cue notes

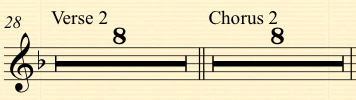

It can also help greatly to mark sections in the parts, even if the players have nothing to do. It helps them keeping track of where they are:

In this image you can see that we have an 8 bar verse, followed by an 8 bar chorus. If the player has to come in right after the chorus, s/he will have no problems finding the entrance.

If you have a song and players have to play only the chorus or so, you usually do not need to write down the exact number of silent bars. Give them a brief decription „Chorus only!“ or something along these lines and make sure to rehearse their entrances.

silent bars in Sibelius

This is where you need to use cues: Look for an easily recognizable part someone else is playing directly before your players have to come in again and write it in the parts in cue notes (smaller notes). The players need to hear the cue part, so choose someone they can hear (very loud, sitting near them, ...) This will help them find the place. Also make absolutely sure the conductor (or whoever may be responsible for leading the players) gives them their entrance very clearly, i.e. by making eye contact one bar before they need to come in.

cue notes

It can also help greatly to mark sections in the parts, even if the players have nothing to do. It helps them keeping track of where they are:

In this image you can see that we have an 8 bar verse, followed by an 8 bar chorus. If the player has to come in right after the chorus, s/he will have no problems finding the entrance.

If you have a song and players have to play only the chorus or so, you usually do not need to write down the exact number of silent bars. Give them a brief decription „Chorus only!“ or something along these lines and make sure to rehearse their entrances.

Give them their first beat!

27/03/11 18:36

One thing that annoys musicians tremendously is composers writing a nice, soaring line for them, but not allowing them to play a last, short note on the first beat of the next measure when their line has ended. Somehow we are internally wired to expect our parts to finish on a first beat. The most prominent example of this is the end of most pieces: After a (lengthy) final cadence they tend to end with a big "bang" on a first beat. Try to compose this way in the whole piece and your players will have much more fun playing your stuff!